“Doctors Won’t Tell You This! – Dark Truth About Antidepressants & How Big Pharma Fooled Everyone”

“Doctors Won’t Tell You This! – Dark Truth About Antidepressants & How Big Pharma Fooled Everyone”

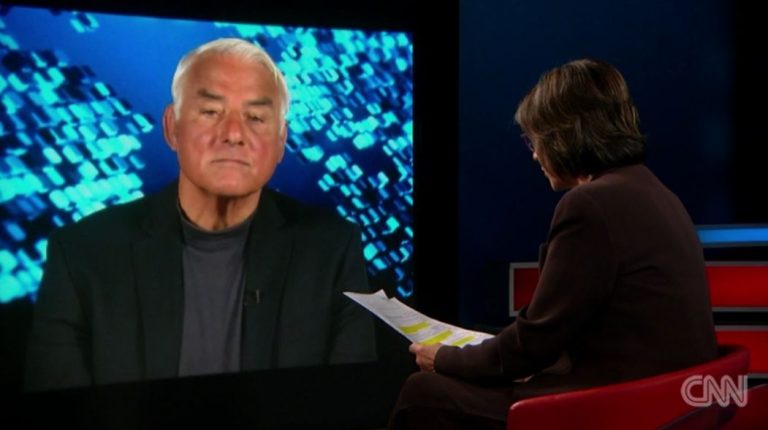

Dr Rangan Chatterjee talks to Prof. Joanna Moncrieff.

CAUTION: If you are taking antidepressants or any other psychiatric medication, do not stop or adjust your dosage without first consulting a qualified healthcare professional. Coming off these medications without proper guidance can lead to serious withdrawal symptoms. Always seek professional advice before making changes to your treatment.

Dr Rangan Chatterjee:

If there is no evidence to support the chemical imbalance theory of depression and a serotonin deficiency, why is it that so many people think that there is and why are so many people on these drugs?

Professor Joanna Moncrieff:

So that’s a very good question and the answer primarily is because of the efforts of the pharmaceutical industry from the 1990s onwards. So, the chemical imbalance theory of depression was first constructed in the 1960s by psychiatrists and researchers who were experimenting with various drug treatments for depression and trying to come up with a justification for using drug treatment in this situation. But it wasn’t an enormously well-known or popular theory at that time. There was a big project set up to test whether there were any differences in people’s brain chemicals, people who had depression versus people who didn’t in the 1980s. That didn’t come up with anything so you know the theory wasn’t really getting anywhere, but then in the 1990s when the pharmaceutical industry wanted to promote their new range of drugs for emotional problems, that is the SSRI, they picked up this theory and widely promoted it. And so there were massive advertising campaigns that told people that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance, or sometimes they’d say it might be caused by a chemical imbalance, but this was repeated so many times that basically people became convinced it was true.

RC: Yeah, this idea that depression is caused by a chemical imbalance, I think that idea has become so widespread that it’s now taken as fact.

JM: Absolutely.

RC: It’s not just oh that’s a theory. I think the general public, or much of the general public, believe this to be true. And so your work for many years including your brand new book Chemically Imbalance: The Making and Unmaking of the Serotonin Myth, I think is really helpful not only for the public but also for professionals like me other medical professionals, who potentially have felt intuitively there’s something not quite right here. But I think what you’ve done is give people the evidence for that or I should say the lack of evidence for that.

JM: Yeah, absolutely. So this is exactly why we set out to do the serotonin review because I became aware that most of the general public think that the link between serotonin and depression is an established fact they think it’s proven, they don’t realize that it’s a speculation, a theory that there may be a bit of evidence for and a bit of evidence against so that’s why I thought right we need to look at the evidence properly set it out get it published and see what it says and I think as you say that actually a lot of clinicians had been persuaded that maybe this was true too even though there was no convincing body of evidence ever put together to say, you know, yes this is definitively the case.

RC: In one of your chapters of this book you write about your appearance on I think This Morning, the UK television show, to talk about this and the resident GP said on that segment, ‘Well, why does it matter? We know that they work it doesn’t really matter why they work’. It was quite shocking for me to read that ‘It doesn’t really matter why they work’. Hold on a minute, there are a ton of side effects to these drugs, so if the whole principle upon which they’re prescribed is built on sand we kind of need to know about it right? So what’s your take on that, for anyone who’s listening and who perhaps is on an anti-depressant at the moment or an SSRI, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, what are some of the signs that might indicate they’re having some problems on them?

JM: So just to say first, it was a very common reaction to when we first published the serotonin paper and also since I’ve published the book for psychiatrists and other leading doctors to say: ‘It doesn’t matter how they work” and I think that is absolutely shocking. I think it matters a lot how they work and it is absolutely essential that we discuss this with the public and so that people are able to evaluate what they might be doing to them if they’re thinking about taking one of these drugs. The idea was that SSRIs would work by correcting an underlying serotonin deficiency and it turns out that actually the evidence for that is weak, inconsistent and not compelling and certainly not proven, but they are drugs, they do change the normal state of your brain chemistry they do modify our biology in some way um and we know that they change people’s thinking and feeling processes and one of the common effects they have for example is that they cause a state of emotional numbing so people often say that they may not feel quite so sad anymore but also they can’t feel happy anymore and they can’t cry and some people might welcome that effect but a lot of people report that it’s actually quite unpleasant and you know they don’t feel like themselves anymore when they’re when they’re in that sort of state.

RC: Yeah, it’s interesting as I was reading your book and diving into your work, Joanna, I reflected a lot on my own practice over the years as a medical doctor and I’ve always believed that one of the most important things that a doctor can give a patient is a sense of agency and autonomy and I feel that by overly labeling people and making them think that they can only get better if they’re dependent on a medication which they can’t then stop, I’ve always had a deep I guess an ethical issue with that and I remember early in my days as a GP there was one patient, I don’t think I started an SSRI on her, I think she’d been started on it by a colleague of mine, but she came in for her four-weekly review and she was a young lady, I think she’s about 23 years old, and I remember her saying to me something to the effect of: ‘Well, yeah, I don’t feel as low as I did four weeks ago, but I feel nothing anymore, I don’t feel high, I don’t feel joy, I feel nothing’. So I always remember that I thought, ‘That’s really interesting, she’s potentially having what you’re calling this emotional numbness or emotional blunting’, and I thought, ‘Well, how is that helpful?’ You could argue we’ve removed the really low moods but if you can’t experience pleasure or joy or hope or whatever it might be, I thought how is this helpful? So that was that one case I really remember super well. The other case I remember really well is, without going into to the young lady’s history, I remember seeing someone and I thought, ‘Yeah, you know, these symptoms are consistent with what we get told we need to hear in order to make the diagnosis of depression’, and I remember looking at the BNF… So for the people listening to the show all around the world, the British National Formula is our kind of Bible of drugs and the consequences what the indications are, what the side effects are, and I remember looking through it and I knew this anyway but I was just looking through it and although it’s documented as a rare side effect I was looking at it going “Oh there’s an increased risk of suicidal ideiation.” And I thought, ‘This doesn’t make any sense to me! I’ve got someone in front of me with low moods and I’m potentially going to be putting her on a drug that, yes, it might be a small risk that may increase her risk of suicidal thoughts’, and I thought, ‘This doesn’t kind of make any sense’. Any comments on what I’ve just said, Joanna?

JM: Yeah, absolutely, it comes back to there being you know two very different ways of understanding what these drugs might be doing and if you understand that they are correcting an underlying abnormality, an underlying deficiency, then it sounds like a good idea to take them and you might take a small increased risk of something if you’re correcting an underlying biological disease that you have.

RC: So if you have an infection for example, a pneumonia which is really bad and you can’t get over it, fevers, productive sputum, all this kind of stuff, you may decide to take an antibiotic, knowing that you may get side effects. I’m just trying to draw the analogy, but do you think that the benefits outweigh the risks?

JM: Yes, exactly, but if it’s not the case that there’s an underlying abnormality and that’s what we’ve shown and you are taking something that changes the normal state of your brain, and your normal feelings and thoughts and behaviors because of that, then the idea that actually some of these changes might be quite negative, like you might get some suicidal thoughts, you might have your emotions. including positive emotions blunted, you might feel lethargic a lot of the time, you are very likely to have sexual dysfunction at least while you’re taking the drug and possibly afterwards, then all these things actually become much more important. They’re not just incidental, they’re part of weighing up whether actually this is a good idea.

RC: And going back to your TV segment where the other doctor said: ‘Well, it doesn’t matter, if they work, they work, we don’t need to know the reasons”. Well, these are pretty significant side effects. Of course we need to know the reasons before we put people on them.

Watch the whole conversation here: